One way I love to keep in touch with the world of words is to go to the theatre. I do it quite a lot. Indeed, I’ve written a few long articles in the past about theatres I’ve known and loved – the Sheffield Crucible and the Liverpool Everyman in particular – but those pieces tended to be about the buildings first, the words and the performances second. I’ve always felt that theatres as physical spaces cast their own spell just as much as the work that takes place within them, but of course, that doesn’t mean that the words that make up each play don’t matter. Unequivocally, they do. And if you want to experience language in its infinite variety, regular theatre attendance is an excellent way to do it.

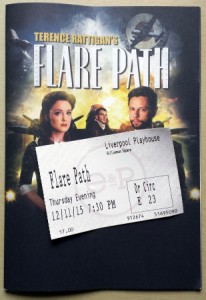

Last week I saw Terence Rattigan’s 1941 play Flare Path at Liverpool Playhouse, a drama set in a small hotel near an RAF airfield during one night in World War Two. The hotel is frequented by airmen and their wives and girlfriends, and when the men are called to carry out a bombing raid on Berlin, we experience the stresses and strains for ourselves – but vicariously, via the partners left at home. While the production itself never quite hit its target – perhaps the piece is simply too of its time to really cut through the fog of the intervening years – I was interested in the way that the brittle wartime dialogue used understatement and euphemism to conceal, and yet also communicate, the extremes of human emotion.

The inability of the British to truly speak their minds was one of Rattigan’s regular themes, but it seemed particularly heightened in this play, dealing as it does with Bomber Command’s terrifying nightly sorties into enemy territory – journeys which for many would turn out to be one-way trips. In our day and age, we might expect that such emotional torment would result in outpourings of verbal anguish, but in Flare Path, there are pursed lips, a few pink gins, and banalities about having to muddle through.

I thought about the way that in my professional world, it’s the precise use of language that matters: the copywriter’s task is usually to convey a specific meaning in an artful yet also functional way. It’s always worth remembering, however, that specific meanings can come in many guises, and in spoken conversation, the words we utter are often filtered through layers of deliberate obfuscation and perceived propriety. During the time of Terence Rattigan’s great success – and of era-defining films such as Brief Encounter, among many others – it seems that inner emotional eruptions could be signified by the use not of highly explicit and demonstrative speech, but by using feeble words – language with its wings clipped. Sometimes, not saying what you mean can serve a purpose, and to a copywriter, there’s more than one way to mean what you say.